Illustration 13. German concertina (chemnitzer).

(from the archive of A. Mirek)

Michal Shapiro proposed yet another scenario in Planet Squeezebox: "There is evidence to prove that it [the bandoneon] was actually invented by a C. Zimmerman of Saxony, who unveiled his invention to the world at the Industrial Exposition in Paris in 1849. . . . This instrument was known as the Carlsfelder Konzertina. In 1850, Heinrich Band, a merchant, advertised the availability of this instrument. There is no record that he claimed to have invented it. . . . However, in Krefeld, it became known as the bandoneon, probably as a fusion of his name and accordion."

The Dutch bandoneon builder, Harry Geuns, seemed to have the most plausible explanation: In 1835 Carl Friedrich Uhlig from Chemnitz built the first German concertina (a large square instrument), not knowing of the smaller octagonal Wheatstone English concertina. Later, Carl Zimmerman and Heinrich Band came out with their own versions, with different button-board layouts. Band was an instrument dealer who did not build his own instruments. The button-board layouts by the three "builders" became known as the Rheinische (Band), Chemnitzer (Uhlig) and Carlsfelder (Zimmerman) systems.

Around the turn of the century in Germany there was a movement for unification, and eventually two systems were chosen: the 124-tone Einheits-Konzertina and the 144-tone Einheits-Bandoneon, although in Argentina the Rheinische system was kept, with sizes of 130, 142 (most common) and 156 notes. Push and pull are counted separately, so a 142-tone instrument had 71 buttons.

In the 1920's, after the acceptance of the unified system, bandoneon bands became popular; the instruments were built in three sizes: piccolo (one octave higher), normal, and bass (one octave lower). One composer of music for bandoneon orchestra was Heinrich Werle, who wrote Aeltere Gebrauchsmusik und Musik zu neueren Volksweisen for four-part bandoneon orchestra. Literature for bandoneon orchestra was published by Verlag Fa. Koster of Berlin, and the Leipzig publishers: Schubert and Co. Musikverlag, Verlag Fritz Kahle and Verlag Viehweg. By 1939 Germany had 686 bandoneon orchestras.

The bandoneon has been called for on occasion by early twentieth-century composers such as Kurt Weill and Heinrich Werle, and more recently by contemporary composers such as Toru Takemitsu, Mauricio Kagel and others. Among Kagel's compositions are Pandorasbox (1960), Aus zungen stimmen (1972), Praeludium fuer Bandoneon and Tango Aleman (1978) for voice, violin, bandoneon and piano. The Japanese composer, Toru Takemitsu (b. 1930), wrote Crosstalk (1972) and the American composer, Gordon Mumma (b. 1935), wrote Mesa (1966) for bandoneon and cybersonic console, and Equale: Zero Crossings (1976) for violin, flute, clarinet, trumpet, tenor saxophone, bassoon, cello and bandoneon. The Belgian composer, Jean Absil (1893-1974), wrote Suite pour bandoneon, op. 121 in three movements: Pavane, Andante misterioso and Moto perpetuo.

In addition, the Argentinean composer, Juan Jose Castro (1895-1968), wrote several pieces for bandoneon including Sonatina para Bandoneon. Virt Maragno (b. 1928) — also from Argentina — wrote Preludio y Fuga and the Italian composer, Giorgio Ferrari (b. 1925), wrote Divertimento.

Two important twentieth-century bandoneonist-composers are the Argentinean Alejandro Barletta (b. 1925) — the father of the classical bandoneon — and his Uruguayan pupil, Rene Marino Rivero (b. 1936). Some of Barletta's original compositions are: Preludios Cosmicos, Luna 1 & 2, Suites para Ninos, Venus 1-18, for various combinations of guitar, violin, bandoneon, cello, piano, flute and percussion, Mars 1-3 for violin, cello, flute, oboe, clarinet, percussion and bandoneon, Jupiter, and 24 Tangos for bandoneon solo. Barletta's compositions for bandoneon and orchestra include: 24 Tangos for bandoneon and symphony orchestra, Doble Concierto for oboe, bandoneon and orchestra, Doble Concierto for guitar, bandoneon and orchestra, and Triple Concierto for violin, cello, bandoneon and orchestra.

Two Spanish composers wrote for Barletta: Joaquin Rodrigo (b. 1901), wrote Moto perpetuo (1960) and Leonardo Balada (b. 1933) — now a U.S. citizen — wrote Geometrias No. 3 (1968), Minis (1969) and Concerto for Bandoneon and Orchestra (1970).

Rivero's compositions for bandoneon and orchestra include: Concierto "De Tacuarembo" No. 1 (1965) for bandoneon and orchestra, Concierto "Los Cuadros De Nino" No. 2 (1982), Concierto "De Montevideo" No. 3 (1995-6), and Dos Movimientos Sinfonicos (1966). He has written over twenty compositions for solo bandoneon, including: Fantasia "El Afilador" (1955), Introduccion y Danza, 1 y 2 (1963), Improvisacion Poematica (1964), Movimiento de Tango (1969), 20 Pequenas Obras Infantiles (1973-6), Estructuras 87 (1987), A Maria Dunkel (1992), Evocacion a Piazzolla (1993) and Mate Amargo con Sergio Prokofiev (1995).

Rivero has written seventeen chamber works which include bandoneon, such as: Adagio (1960) for violin and bandoneon, Preludio y Danza (1964) for violin and bandoneon, Epilogos (1969) for bandoneon, violin, trumpet and contrabass, Memorias No. 1 (1973) for viola and bandoneon, Paraleon (1977) for oboe and bandoneon, Bacterias No. 1 (1971) for violin, guitar and bandoneon, Tres Movimientos de Tango (1980) for bandoneon and guitar, Tres Piezas para Trio (1981) for bandoneon, violin and guitar, Estructuras (1986) for soprano, guitar, bandoneon, piano, clarinet, contrabass, trombone, and percussion, and Fantoches (1989) for bandoneon and guitar. He has also written two pieces for bandoneon and tape: Juegos Extranos (1977) and Impresiones de Toledo (1986).

Although there have been many great exponents of the instrument, such as the Argentino bandoneonistas Eduardo Arolas (El Tigre del Bandoneon), Anibal Troilo (the great teacher), Pedro Laurenz, Pedro Maffia, Leopoldo Federico, Nestor Marconi, Juan Jose Mosalini, Dino Saluzzi, the Dutch Karel Kraayenhof and the French Olivier Manoury, the person who, more than any other, lifted the bandoneon from the dance hall to the concert stage was the performer-composer Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992). Due to his Argentinean culture and birth, he spent much of his youth performing tangos. As a young man, however, he abandoned the tango and began classical compositional studies with Argentina's Alberto Ginastera and France's Nadia Boulanger (who taught both Aaron Copland and Philip Glass).

Gerald Seligman wrote, "Finding his [Piazzolla's] classical compositions lacking in depth of feeling, she [Boulanger] reputedly asked him about his own traditions. When it finally occurred to him to play her one of his own tangos, she replied, 'This is Piazzolla. You must never abandon this.' Under her tutelage she coaxed him to join his two external influences, that of classical music and his love of American jazz, to his native tango.

"It was Piazzolla's dream to create a tango that would not only be dance music but concert music as well. 'For me,' Piazzolla said, 'the tango was always for the ear rather than the feet.' The results were as audacious and innovative as they were outrageous to prevailing trends. For in Argentina, you don't mess with the tango and go away unscathed. As a beloved music that helped to define a largely immigrant people, to give them a newfound identity in rough times, messing with the tango was messing with the fledgling national character."

Seligman continued, "So when Piazzolla returned to Buenos Aires from trips abroad, taxi drivers recognizing him through their rear-view mirrors would harangue him, while others pulling up to the curb pulled right back out again. Musicians even came to threaten his life. A few once waited for him outside his house to work him over. One tango singer actually barged into a radio station where he was giving an interview and put a pistol to his head. 'I was taking the old tango away from them,' Piazzolla said. 'The old tango, the one they loved was dying. And they hated me.' But he took nothing away from them at all. By modernizing the form, by midwifing the birth of a far more profound music within the tango, Astor Piazzolla made it more eternal." Piazzolla wrote over 750 compositions, including concerti, operas, film and theater scores, and made over seventy records.

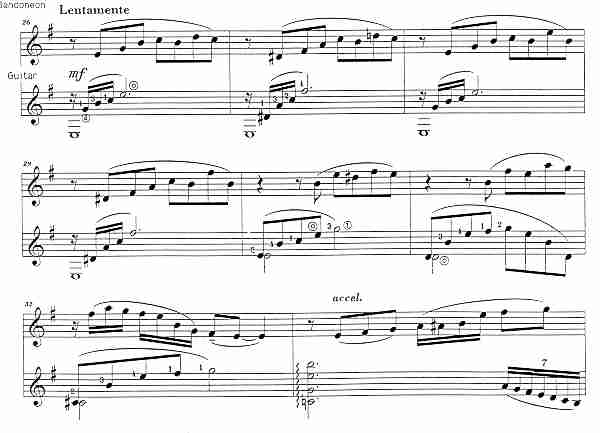

Example 7. Astor Piazzolla, Double Concerto for bandoneon, guitar and

string orchestra,

measures 26-33 of the bandoneon and guitar part.

©

1981. Used by permission of Editions Henry Lemoine, 24 rue Pigalle,

F-75009 Paris.

| Back to History of the Free-Reed Instruments |

| Back to The Classical Free-Reed, Inc. Home Page |